Annie O’Neill has just finished delivering a session in which she has taught year 13 students to manage their anxious “glitter mind” with breathing exercises, CBT techniques and mindfulness. When the school nurse finishes, one of the students shyly shuffles up. After a long pause, she says: “I have a lot of pressure on me. All the time I have a voice in my head saying I’m not good enough.”

The student is a high achiever with an offer at a top university and a supportive family, yet she cannot shake the feeling that although she spends so much time revising, nothing is going in. She has not spoken to anyone else about how overwhelmed she is feeling.

“You say ‘I’m coping’ but really you’re like a swan, serene on the outside, with legs paddling frantically underneath,” says O’Neill, giving the tearful student a hug before she heads off, having agreed to speak to a teacher and a doctor.

For O’Neill, this demonstrates the value of school nurses: they are trusted adults who are independent from the school, meaning students feel more comfortable sharing confidences with them. They can signpost services, and prevent today’s stress from becoming tomorrow’s mental health crisis.

School nurses are having to do this more often. Mental health problems among children were on the rise prior to the Covid pandemic, and lockdowns have resulted in more behavioural problems, while teacher-graded GCSEs mean year 13s have never experienced exam stress.

O’Neill used to work as a school nurse employed by the local authority, but five years ago she went independent after she became exasperated with only having time for child protection cases, and not preventive health and wellbeing work.

She is employed by the Unity Schools Partnership and spends one day in each of its 33 schools every term. Nearly two-thirds of those schools appreciate her work so much that they claw shreds of funding from their pupil premium, PSHE and CPD budgets to pay for additional sessions.

On this day, she is at St Edward’s academy in Romford, east London, where 27% of children are eligible for free school meals. Seeking to prevent pupils from being among the “lost children” who dropped out of school during and after the pandemic, its leaders are prioritising a preventive approach to mental health.

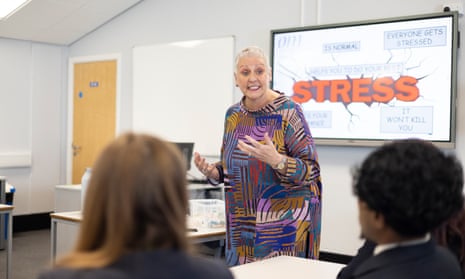

O’Neill’s sessions for GCSE and A-level students teach them that stress is a natural response, and that negative thoughts about failure do not always reflect reality and dwelling on them can make them self-fulfilling by encouraging avoidant behaviours.

“Where is the evidence it’s true?” she asks, asking students to think about their results in their mocks, what their teachers tell them about their abilities, and how much revision they have done, and then do something that makes them feel better, whether that is ice skating or playing video games.

Anxiety is clearly a problem for all the students. When she asks a class of nine year 11s which of them are anxious, six raise their hands. She asks how many have had panic attacks, and the same number answer affirmatively.

“There’s been a huge rise in eating disorders. Kids who don’t know what healthy relationships look like, can’t negotiate friendships, and romantic relationships, they don’t know what normal is because they’ve been consuming lots of stuff online,” O’Neill says.

For younger children, O’Neill has been asked to put together a session on school readiness. “Children are coming into school in nappies, never having eaten solid food, still using dummies,” she says. She is also helping Unity with a research project around how to improve attendance post-pandemic, including persuading parents of school’s value.

Jodie Hassan, the school’s headteacher, says hiring O’Neill was part of a concerted effort to “build back” after the pandemic and support children “who now feel ‘what’s the point?’. Who are disconnected and disenfranchised.”

“During the pandemic, we put at the top of the list wellbeing,” she says. “The finances in any school are disastrous, it’s not that we have money we can spend, but we thought we can’t not spend the money … everything hinges on your wellbeing.”

She adds that “we try to prevent as much as possible”, especially since her safeguarding teams who put forward children to child and adolescent mental health services (Camhs) have seen “wait times have gone through the roof”.

If money were no object, Hassan would like O’Neill and her business partner to be full-time members of staff, with a team of their own. “I’d put them in every classroom, walking the corridors, ready to look after any child or adult that needs it. If we had more [staff], we could pre-empt what was going wrong before it went wrong.”