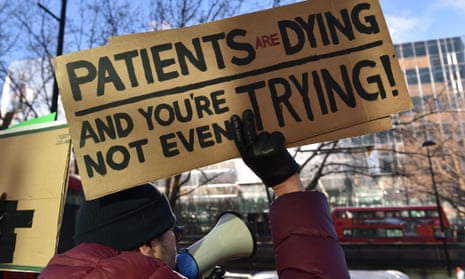

Crisis, conflict and collapse have driven the NHS to the top of the political agenda. Every day brings new horror stories from the frontlines of a health service on its knees. Yet there is no evidence of urgency from the government, which seems determined to weather the winter struggle while handing out as little cash as possible to hospitals and staff. They may come to regret this. An unprecedented healthcare crisis poses unprecedented electoral risks on a broad front.

The first of these is already obvious in the daily news rounds, which are now dominated by NHS stories, none of them good for the government. Polling shows rapid rises in the share of voters rating healthcare as an urgent priority. The dangers from this rise in salience are magnified because much of it will be driven by direct experience of a collapsing health system. Changing the focus of the media narrative won’t do much good when hundreds of thousands of voters are seeing the crisis for themselves every day.

These voters know who to blame. Health services in general, and emergency health care in particular, are universally seen as a basic responsibility of government. Past Conservative governments have found ways to shift the blame. Spending squeezes in the coalition era could be blamed on the financial crisis and the previous Labour government. That line no longer works. The current mess in the NHS comes after a decade of Tory rule, and the current fights with healthcare unions are fights the government has chosen to pick. There is nowhere to hide.

A wave of public anger over healthcare also poses special risks to the Conservatives due to their longstanding reputation as a party that cannot be trusted with the NHS. Voters have preferred Labour over the Conservatives as stewards of the healthcare system in almost every poll on the issue for decades.

The current crisis reinforces longstanding suspicions. “You can’t trust the Tories with the NHS” is a staple attack line of every Labour election campaign. The line will have real bite next time.

With failure posing dire electoral risks, the government urgently needs a way out, but it faces constraints that look set to frustrate progress at every turn. Holding the line on pay or taking action against striking unions will deepen the worst recruitment crisis in NHS history, but accepting a larger pay rise will require spending increases the Treasury opposes and tax rises that infuriate Tory backbenchers.

The appalling wait times for ambulances and A&E treatment cannot be fixed without freeing up beds, but freeing up beds requires fixing the crisis in social care. Rishi Sunak ditched a promised tax increase to fund social care to appease tax-averse Conservative MPs, and kicked plans for reform of care costs into the long grass. With the social care crisis unaddressed, the prospects for improvement in the NHS are dim.

Yet even if the political will could be found to push through the huge resources needed to fix things, it is too late to deliver results. A decade of underinvestment in staff and infrastructure cannot be turned around in two years. Perhaps some vacancies can be filled, mountainous backlogs brought down a little, and wait times shifted from dire to merely awful. But it will be too little, too late.

For even if the worst of the storm passes by election day, the searing memories of the current crisis will endure. Ambulances taking hours. Elderly relatives on trolleys. Long, anxious waits in chaotic A&Es. The nausea of not knowing when, or if, help will come. Those who lived through this will not forget it. And they will not forgive it.

Robert Ford is professor of political science at Manchester University and co-author of The British General Election of 2019

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion