In recent years, scientific endeavor has enabled us to produce a ‘picture’ of a black hole. An astronomical phenomenon that heretofore was thought to be purely theoretical in nature. We couldn’t see them, and debates raged as to whether or not they existed. What helped scientist to ‘discover’ them, and to eventually locate one and study it, was to look at how things interacted with them and around them; examining the ‘edges’ and building up a picture of the ‘space’ that was missing.

In many, ways, it can help to think about black holes when we think about the societal phenomenon, and personal experience, of childhood sexual abuse. We often cannot see it directly and can only tell that it is there by examining the ‘edges’… how things interact and behave around it. For adults coming forward to disclose childhood experiences of abuse, responses that include delay or uncertainty can often cause impacts such as anger, hostility, silence, submission, anxiety, shame, or stigma. Akin to the essence of trauma informed care, these are things we can often see, and feel, and experience; things that should draw our attention to the potential presence of something deeper.

In 2015 I conducted fieldwork for a project called How Adults Tell. This was my PhD research which examined adults’ experiences of disclosing childhood sexual abuse to the child protection services in Ireland. The study used a narrative methodology to explore the lived experiences of engagement with a system that was struggling to manage adult disclosures. The findings from that study, published this year, showed that adults were unclear as to what would happen their disclosure to child protection services, unclear as to who might get told about their report, and unclear about when family members or members of their community, identified in a disclosure, might be notified or be approached, and what might happen next. The main themes emerging from that research were that the system itself acted as a barrier to adults coming forward, the dynamics of abuse and disclosure (power in particular) were not appreciated by services and their underpinning policies and practices, and finally that victims and survivors’ experiences and voices hold key messages for how the system can become a facilitator.

In the interim however, policy developments in respect of retrospective disclosures, and the practices on foot of them, have come under the scrutiny of the Office of the Ombudsman, HIQA, the Department of Children and Youth Affairs, and most recently our Governmental Rapporteur on Child Protection. The interim period, between the data collection and today, also saw the commencement of our mandatory reporting laws and the integration of the European General Data Protection Regulation into Irish law. A lot of change, some good, some not so good. It therefore seemed important to revisit the issues and examine what adults’ current experiences are of coming forward to meet social work services; to examine how best we can aid retrospective disclosures of childhood abuse.

Between May and December 2020, an anonymous online survey was conducted to gather adults’ experiences. The study was funded by the Irish Research Council and UCD Seed Funding and ethically approved by UCD Human Research Ethics Committee. The survey was designed in consultation with a panel comprised of members of One in Four, the Dublin Rape Crisis Centre, and the Rape Crisis Network Ireland and sincere thanks goes to each organisation for their support and advice. Sincere thanks also goes to all those who took the time to participate and share their experiences.

A note on the response rate: The study was conducted between May and December 2020 and was therefore impacted by the covid-19 pandemic in terms of delays and participation rate. Added to this, a skip-logic process was used throughout the survey, meaning that participants were only presented with those sets of questions that were applicable to their individual experiences. For example, only those who identified that they had received contact from child protection services were directed towards the set of questions dealing with this aspect. This meant that while the survey received 29 responses in total, some sections received less responses due to the use of the skip logic section. The rationale behind this was to reduce the risk of overburdening the participants and to ensure that the participants were only responding to questions that were relevant to them.

The full report will be publicly launched at an event in October and a more comprehensive academic paper will follow. Included below is a very brief synopsis of some of the topline findings of the study and a snapshot of what adults’ current experiences are when coming forward to make retrospective disclosures of childhood sexual abuse.

Latency to disclosure:

Responses to the survey reflect the wider international research in that those who disclosed, tended to delay disclosure. A majority disclosed over ten years after their experiences of abuse. Reminding us to expect, and prepare for disclosure in adulthood and later adolescence.

Understanding the process:

Participants were asked to what degree they agreed with the statement that they understood the process. Of those who did engage with child protection services to make a retrospective disclosure, a majority expressed that they did not understand the process and some (n=3) were not informed that they could bring a support person with them when meeting with child protection services.

Being kept up to date:

When asked if they were kept up to date about the assessment of their retrospective disclosure, a majority of those who participated felt that they were not kept up to date…

The EU Victim’s Directive:

Using the language of the EU Victim’s Directive, a section of the survey also asked respondents if they were offered any of the following information without undue delay:

• the type of support that could be obtained and from whom;

• the procedures for making a complaint;

• how and under what conditions one could obtain protection;

• how and under what conditions one could access legal advice, legal aid and any other sort of advice;

• specific details of services related to sexual abuse counselling, therapy, advocacy or support;

Twelve participants responded to this section. Three of the twelve were offered information regarding how to make a complaint. Of note, only one person was provided with specific details regarding support services related to sexual abuse, while a majority of respondents in this section (67%, n=8) answered that that received none of the above advice.

(A more detailed examination of the provisions of the EU Victim’s Directive will feature in the full report and subsequent academic paper.)

Information sharing:

Significant issues have been raised in terms of how adults’ information is being safeguarded and used in the process of assessing retrospective disclosures, with some therapy and advocacy organisations raising the point that such concerns may potentially put people off from coming forward for support in the first place.

In terms of such data protection, GDPR, and information sharing, a majority of participants in the study were not told that their information would be shared with someone else during the assessment process…

… and at the time of the study most were unsure whether or not any of there information had been shared.

If starting over:

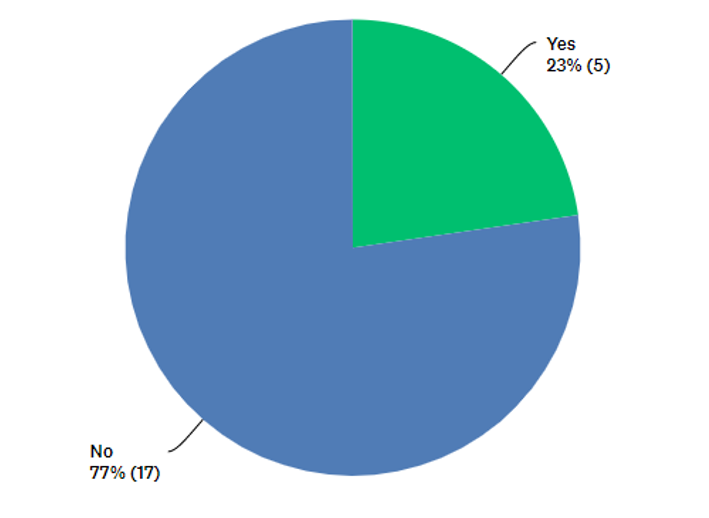

Twelve respondents chose to complete the section relating to their overall experience of engaging with CPS. Unfortunately, when asked “If starting over, would you engage in this process again (your disclosure and, where relevant, your engagement with TUSLA)?”, most stated that they would not. Posing questions for how we develop policy, services, and responses in this area of practice.

The participants of this study largely felt they did not understand the process of what would happen once they reported to Tusla. Most were contacted by a letter in the post to acknowledge the receipt of their report. However, following this initial contact, most felt that they did not understand the process or what would happen next. Many were not provided with any written material attempting to explain this. How Adults Tell showed that the point at which their story or narrative was handed over to child protection services tended to be a critical point at which the dynamics of power and control came in to play, significant features of abuse in childhood. The participants of that previous study spoke about the anxiety and stress leading up to sharing their experiences with social work services and the feeling of a loss of control once their disclosures had been handed over. The lack of information or lack of clarity following this being described as a black hole, a void, or falling off a cliff. It appears, from the results of this survey, that many may still be experiencing this black hole.

Moving forward together…

Much like those scientists who located that black hole, their endeavors required the collaboration of an array of telescopes scattered across the globe. All perfectly aligned and in sync, pointing the same direction, with the same focus and aim. Responding to and supporting adult victim and survivors of childhood sexual abuse should not be viewed as the job of one agency. The Child and Family Agency has a distinct set of important skills that perfectly position it to add to the fight in this area, but more resources, training, understanding, and services are required. It is also acknowledge that Tusla are in the process of reviewing their policies and practices in this area and the voices of those impacted and those services supporting them need to be key contributors to this process of review.

We still require a legal underpinning for social workers to do their jobs in this area. We still require a comprehensive and robust process of data management and sharing. We still require appropriate funding and resources for therapy and advocacy services so that waitlists can be adequately managed and reduced. We still require clear and robust frameworks of practice that can hold competing legal and human rights in tandem, while firmly acknowledging and accounting for the potential life long impacts of childhood sexual abuse. Will still need an ethic of care to be a starting point in any such work.

I have been researching this area of Irish social work policy and practice for ten years, there remains a long way to go, but what remains ever clear is that the voices and experiences of those going through the system are the key to unlock where we should go next.

**This piece serves to flag the forthcoming report, launching on October 8th 2021. Registration details for that event will be available in early September 2021. The above piece is a snapshot and does not provide the methodological or analytical details related to the study, only a small selection of the findings have been presented here and should be viewed, or used further, with that in mind. Sincere thanks once again to the 29 participants, One in Four, RCNI, Dublin Rape Crisis Centre, the Irish Research Council, and UCD Seed Funding.