I live 10 minutes’ walk from a disused psychiatric hospital in north London. Well, partly disused: 40% of St Ann’s in Tottenham, with the glossy new assessment centre and low-rise 30s blocks, is still going strong. The other side of the site, built as a fever hospital in 1892, has been gradually abandoned.

There is a Victorian laundry, grand as an ocean liner. A massive castellated water tower, like the rook in a giant’s chess set. A gorgeous sprawl of red-brick wards and lodges, with shaped gables, stacked chimneys and blind boxes over intricate windows.

A wildlife survey in 2019 found hare’s foot fungi and 59 species of spider. The grounds are full of wild flowers and trees: strawberry, rare in the UK; mulberry; spotted thorns; and scores of true service trees – the legacy of an ambitious gardener poached from Kew in the 1920s.

There are traces of former patients, too. I found an ancient belt buckle in the soil near the railway line. On one external wall are names inscribed in cursive script in the soft terracotta. My son and I spent a lot of lockdown exploring. We rarely saw anybody else, although ghosts never seemed far off.

Then, in November 2021, huge trucks arrived. The long-threatened property developers? No: a film crew, meaning the wards were scrubbed down and abruptly filled with acting veterans of the highest rank. I turned up one cold morning and walking down the ornate outdoor corridor, so recently filled with traffic cones, came a heavily bruised Julia McKenzie in a nightie.

Judi Dench was also there, in dressing gown and slippers. “It’s very, very strange,” she says. “I think with a building that’s been a hospital or a school, you always feel that kind of presence. But because it’s so potent at the moment, it is a very strange feeling. I wouldn’t have believed they would be able to find a room. You suddenly think: why are there these empty wards?”

The film Allelujah, adapted from Alan Bennett’s 2018 play of the same name, shot as Omicron first made headlines. No one knew if this would be the variant to return us to square one, or worse. Hospital admission rates rocketed, mask rules were reintroduced. “You don’t know if it’s today or tonight or next week,” said Dench. “It is a curiously odd sensation, because everything is so uncertain. It’s made me feel deeply anxious.”

I spoke to Dench, then 87, in her trailer after seeing her shoot a scene: an incredible treat and slightly disquieting. “I think it’s all deeply depressing, I’m afraid,” she said, eyes bright. “I’ve completely lost my rhythm inside.”

She quoted Viola’s “pined in thought / with a green and yellow melancholy” speech from Twelfth Night. “I’ve always thought that’s such a strange thing to say. But now I understand.” Shooting a film that was set pre-Covid offered brief relief. Likewise, a recent trip to Marks & Spencer for Percy Pigs and a sweater: “Just heaven!” But she doubted being able to repeat the treat anytime soon. “You don’t dare put on the radio, because you don’t know what’s going to happen next.”

In Dench’s case, it was an Oscar nomination for Belfast. Three months after we met, she was on the red carpet in Hollywood, the oldest-ever best supporting actress contender. She ended 2022 playing pianola for an impromptu Abba singalong in Braemar with Sharleen Spiteri. Next month, she will be at the Palladium for a gala celebrating Gyles Brandreth’s birthday (proceeds to Great Ormond Street).

March will also see the release of Allelujah – timing designed to tee up the 75th anniversary of the NHS. Bennett’s play is set on the geriatric ward of a Yorkshire community hospital called the Beth, which is earmarked for closure. Dench, along with McKenzie, Derek Jacobi and David Bradley, play patients; Bally Gill the benevolent Dr Valentine; and Jennifer Saunders the pragmatic Sister Gilpin, continence her guiding star.

Allelujah’s director, Richard Eyre and Dench have history here: not just Notes on a Scandal and The Cherry Orchard, but Iris, the award-winning film about Iris Murdoch’s descent into Alzheimer’s. The patients at the Beth are fairly unaffected mentally – unless you count the chronic Bennett-isms. In fact, they are in fairly good nick: in need of care, but not palliative. Mostly mobile, highly responsive to tea and cheer.

It’s the sort of institution familiar to Eyre from the experience of his mother, who spent 10 years in an exemplary county hospital in Dorchester. “The care was wonderful. The nurses loved her,” he says, sitting swaddled in a ski jacket in an old storeroom at St Ann’s. “But then they changed the policy and said: ‘We’re not having geriatric incurable.’ So they pushed her out to a care home. She was dead within a week.”

Allelujah is most conspicuously about the NHS. But it’s also a film about social care: what happens when pressure on hospital beds means people are discharged too soon, to inadequate accommodation.

“When I grew up, everywhere in the south of England seemed to be a convalescent home,” says Saunders, curled up in her trailer at St Ann’s with Olive the whippet. “There was a stopgap. Back then, everyone died in their 70s. We haven’t produced any new thinking.”

Eyre turns 80 imminently. When we caught up last month, he had been reading about half-hour home care visits that were actually three minutes: “Probably very common.”

He continues: “I’m in a privileged position. If I’m unable to look after myself and my family can’t, then I’ve probably got enough money to go into a private care home – and there are some really good ones.” There are also some very poor ones. “There’s always going to be a demand, and if they can provide the minimum care for the maximum income, that’s business.”

This became especially glaring in the early days of Covid, “when the instructions were to decant geriatric patients from hospital into care homes. It was like detention camps! What did they think was gonna happen? Doctors didn’t go in. The homes clearly couldn’t cope. They’re stretched or inadequate at the best of times. A lot of people died.”

Earlier this week, I got an email from Dench. Her abiding memory of Covid, she wrote, was hearing of a close friend unable to enter her mother’s care home. “She had to stand at the window to wave at her mother, and sadly that was the last time she saw her. That will haunt me for ever.”

Dench lives with her daughter, Finty, 50, and Finty’s son, Sam, 24, in the same house she bought 40 years ago with her husband, Michael Williams, so they could accommodate their own parents (it was funded by a Clover butter ad). “It was very successful,” she says. “We had to work very hard at it, but my ma and my parents-in-law were very comforted by the fact that we could all be together.”

This is a rare setup. Bennett’s play doesn’t shy from showing how grasping or unfeeling less loving relatives can be. Most are simply absent; patients at the Beth, abandoned to the system, tend not to get visitors.

It’s a sharp critique of an intractable problem, says Eyre. “I don’t see how any government can change the culture of families to make them more caring. You accept this is the world we live in, so what are we going to provide for those people who have been disfranchised?” Anyway, the Tories seem “curiously insulated” from the issue. “It’s strange: surely they must have parents or relatives who are in care or suffering?”

Maybe they just don’t care? “That’s perfectly possible.”

It’s his own generation’s fault, says Eyre. “We fetishised being young. ‘Hope I die before I get old’ – it’s just stupid! There’s no need for us to make such a fuss of the young, to keep mimicking them, showing how envious we are.”

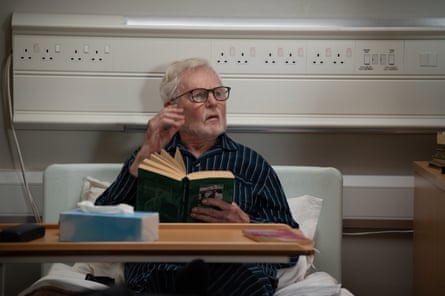

Allelujah does not. We see actors of huge fame and familiarity, in their late 80s, looking their age. For Gill, who is 30, this was disconcerting: “Especially Judi. I used to see her in my mind as M from the Bond films. But this was a very vulnerable, fragile, quiet character.” Seeing her with cardie and cannula was “was quite shocking, even for me. I was like: wow, OK.”

In the first scene of the film, we watch Dr Valentine chat over his iPad with his family back in India: mothers, aunties, nieces, a grandmother to whom he has sent a scarf. It’s this upbringing, the film gently suggests, that has encouraged in him a respect for elderly people.

“It is a little bit different in Indian culture,” says Gill. When he shot the film, he had never been in an actual geriatric ward. But he spent a lot of last year in one, visiting his grandmother, who recently died of cancer.

The family found being by her bedside essential, he says. “We had to actively say: look, she needs pain relief. And she needs to have a proper, decent meal. We ended up feeling quite pushy. The system is so strained. We were on them constantly.

“If you’re not kind of pushing, you’ll be forgotten. I did feel sorry for the people who didn’t have family members coming in. There is a feeling, when you get to a certain age, that you have nothing left to provide.”

Eventually, his grandmother was able to be discharged. “As a family, we would rather have her with us. So we looked after her in those last stages of her life and really tried to come together as a community.”

He couldn’t have made the film now, he says: “It’d be a bit too emotional.” Partly because the story is so similar to his grandmother’s, partly because it’s so different. Thanks to the speed of change, Allelujah can already feel like a period piece. “What Alan Bennett created is a very different world to what actually is happening and what that care actually looks like,” says Gill.

Back in 2021, the cast and crew all expressed hope that Covid would reboot the NHS. More funding, more cheerleaders for its mission. Those first-wave discussions about whether younger patients should be prioritised over older, were resources to become sufficiently stretched, raised “a perfectly legitimate question”, says Eyre. “In Sweden, there is a sort of explicit rationing, and I’m quite in favour of that, because you know where you are, rather than this constant saying: what the NHS needs is more and more money. I’m sure it does, but it also needs clarity of what we are fighting for.”

Even Dench was darkly pragmatic: “I suppose if you’ve had your four score years and 10, you’re going to drop off the bough anyway.” But, on the bright side, “maybe those barriers [between medical and social care] have broken down a bit during Covid. I hope they have. So perhaps a very good thing will come out of it.”

Expectations have since sunk. Meanwhile, the film’s final scene has taken on more weight. This coda, an add-on from Bennett’s play, shows Dr Valentine working in an ICU ward in April 2020. He addresses the camera, imploring support for the NHS. “It’s a wholly utopian plea,” says Eyre. “And, to some extent, it’s what the film feels. I find it immensely moving.”

Saunders says when she first read the script, she wasn’t sure that scene would work. She changed her mind: “You realise how quickly the sacrifices made by medical staff are forgotten.” Dench agrees: “We willingly clapped on our doorsteps our appreciation for the NHS, as they were doing a remarkable job. That seems to have been a bit forgotten. And look at the position they are in now, having to strike for more money.”

On Monday, public access to 60% of St Ann’s was permanently blocked. Soon, the buildings will be demolished for a £200m high-rise development. Work has already begun bulldozing at least 50% of the foliage – shortly before Haringey council (who signed off the deal, and declared a Climate Emergency in 2019) publishes its latest Tree and Woodland Plan, highlighting the lack of green provision in the borough.

There is talk some of the inscribed bricks may be saved. I don’t hold out much hope for the spiders.

Allelujah is released on 17 March

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion