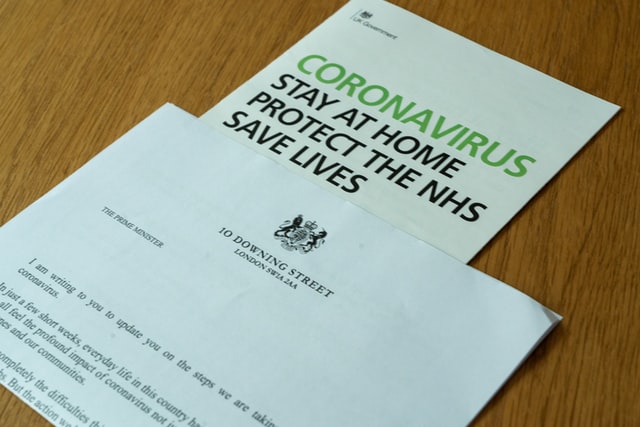

No-one needs reminding that we have been living in unprecedented times (although plagues such as the Black Death probably do set a precedent). Social care has probably never had so much attention from politicians, the NHS, public health, or the media. But stories can get forgotten and so research is helpful in providing a platform for reporting views and experiences or the testimony of those affected. This blog reports on a study by Nyashanu and colleagues (2020) that captured some of the frontline experiences of social care work during the early and dreadful weeks of the first national lockdown in England arising from the spread of the coronavirus or COVID-19.

This blog reports on a study that captured some of the frontline experiences of social care work during the early and dreadful weeks of the first national lockdown in England arising from the spread of the coronavirus or COVID-19.

Methods

Data for this study were collected online (by Zoom, FaceTime, WhatsApp). One-to-one semi-structured interviews were undertaken with 40 social care staff of whom 15 were support workers, 15 were nurses and 10 were managers (N = 10). They were working either in home care/domiciliary care (15 participants) or care homes (with and without nursing) (25 participants) in the West Midlands region of England. More than 30 social care employers were approached by the research team, of which 20 agreed to take part in the study and to send their staff the invitation to take part in the study. The interviews took place between February and April 2020 – the time of England’s first national lockdown and they were recorded, with permission, and transcribed for analysis.

Results

The research team identified nine themes arising from the interviews. They present a brief discussion of each, with several illustrative quotes, and a note of what proportion of the three staff groups (managers, nurses and support staff) identified each one. This helps see the common experiences or differences between the three main job categories. Everyone mentioned lack of pandemic preparedness and shortages of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and delays in testing, evolving (changing) PPE guidance, and shortages of staff or colleagues, with near universal common admissions of feelings of anxiety and fear amongst professionals (only 2 managers did not mention this). In terms of the other themes these three were mentioned by all the nurses and support workers:

- challenges in enforcing social distancing;

- challenges in fulfilling social shielding responsibility;

- feelings of anxiety and fear amongst residents and service users.

Some managers did not raise these points, but most did. This suggests that the broad social care sector – home care and care homes – was experiencing very similar problems and that these were encountered by support staff in care homes as well as the care home nurses, and mostly by their managers.

Everyone mentioned lack of pandemic preparedness and shortages of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and delays in testing, evolving (changing) PPE guidance and shortages of staff or colleagues, with near universal common admissions of feelings of anxiety and fear.

Conclusions

On the basis of their findings, the research team argues that pandemic preparedness is a missing part of social care and should be rectified – through mandatory training for social care staff and direction from central government and public health bodies. They argue for stocks of PPE to be maintained and for social care staff to be given priority for testing. More broadly, they refer to the need to reform social care so that funding problems and staff shortages are resolved. Mental health support for staff should also be available.

On the basis of their findings, the research team argues that pandemic preparedness is a missing part of social care and should be rectified – through mandatory training for social care staff and direction from central government and public health bodies.

Strengths and limitations

As the researchers note this study was confined to the West Midlands and experiences might have been different elsewhere in the UK. The strength of the study lies in its coverage of care homes and home care services and the fact that the interviews were done at the time of the height of the pandemic in its first wave in the UK. The sample size is sufficient for a qualitative study especially considering the stress that the participants were likely under. It may have been helpful to them to be able to tell their stories.

Implications for practice

We are all likely to hear stories from people working in social care about their experiences during the peak of the pandemic in early 2020 and this paper provides a collection of accounts in which to contextualise individual experiences. It may be helpful to discuss the research with practitioners to see if these experiences resonated with their own; with due caution not to evoke distress. While there has been more political and media attention to the situation of care homes, this paper suggests a commonality of experience in the frontline between care homes and home care staff. The latter work more in isolation and so recommendations about increasing their support may be more pertinent.

While there has been more political and media attention to the situation of care homes, this paper suggests a commonality of experience in the frontline between care homes and home care staff.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest

Links

Primary paper

Mathew Nyashanu , Farai Pfende & Mandu Ekpenyong (2020) Exploring the challenges faced by frontline workers in health and social care amid the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of frontline workers in the English Midlands region, UK, Journal of Interprofessional Care, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13561820.2020.1792425 published online 17 July 2020.

Photo credits

Photo by Stefano Intintoli on Unsplash

Photo by Macau Photo Agency on Unsplash

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash